The “hive mind” effect shows that being around really smart people can help to bring out the best in you. Our capabilities are often closely tied to the intelligence and abilities of the people around us.

IQ is one of the oldest and most tested measures in all of psychology.

While IQ isn’t a perfect measure of intelligence, most research has found it to be strongly associated with a wide-range of mental ability including memory, attention, reaction times, and problem-solving.

Many of these general mental abilities translate in the real world into the form of higher incomes, higher social status, better job performance, and even better relationships.

In the new book Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own, economist Garett Jones discovers that IQ at a national level might be even more important than IQ at an individual level.

Throughout the book, Jones describes the synergistic effects of being surrounded by high IQ people. He calls it the “hive mind” effect. And in fact, due to this “hive mind” effect, it might be better to be a “less intelligent” person in a “high intelligence” group rather than a “more intelligent” person in a “low intelligence” group.

As Garett Jones describes it in the book:

- “It’s typically better to be the less-skilled honeybee in the highly productive hive than to be the highly skilled honeybee in the less-productive hive: your neighbors have an important influence on what you can accomplish.”

A group of smart people can often feed off of each other and become more than the sum of their individual parts. They bring out the best in each other – and this is just as true for a business or organization as it is for a nation as a whole.

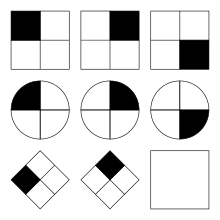

While there is still a lot of controversy on what determines IQ, and to what degree the tests are culturally biased, many current forms of IQ tests such as the “Raven’s Progressive Matrices” test doesn’t involve any language or cultural knowledge to partake in.

Here is one example of a question in this type of IQ test:

Based on the patterns of the first two rows, what figure should be in the empty box?

This is an easy example, but gradually the questions become more complex and sophisticated. (Although the questions are typically multiple choice).

The main goal of this type of IQ test is to recognize patterns – and believe it or not, being able to identify these patterns can be a fairly reliable measure of general cognitive ability.

Using IQ data from all over the world, Garett Jones finds that there is a strong correlation between national IQ scores and economic growth. According to his research,

- “On average, nations with test scores in the bottom 10 percent worldwide are only about one-eighth as rich and productive as nations with scores in the top 10 percent.”

Of course, correlation doesn’t equal causation. It’s well-known in IQ research that impoverished countries can suffer from abnormally low IQs due to lack of nutrition, lead exposure, or a “scarcity mindset.”

For example, one study shows that Indian sugarcane farmers often score between 10-15 points lower on IQ tests pre-harvest rather than post-harvest. A “scarcity mentality” can often lead to stress and anxiety that hurts our mental abilities.

In this sense, low IQ and poverty can become a vicious self-fulfilling cycle.

However, with this being understood, the rest of the book does an excellent job looking into how IQ in-itself can be a cause of more successful and prosperous nations.

I’d like to cover some of these big ideas throughout the rest of this article. They can have important implications for building better nations but also better organizations on a smaller scale, as well as improving our own lives by encouraging us to spend more time with smarter people.

Smarter people are more cooperative

One of the most interesting findings in the book is that high IQ people are more cooperative than low IQ people.

The most common way to measure cooperation in psychology and economics is through a popular test in game theory known as “prisoner’s dilemma.”

First, let’s go over the “prisoner’s dilemma” real quickly in case you haven’t heard of it. Here is one common form of the game as described on Wikipedia:

- “Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of communicating with the other. The prosecutors lack sufficient evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge. They hope to get both sentenced to a year in prison on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the prosecutors offer each prisoner a bargain. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to: betray the other by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the other by remaining silent. The offer is:

- If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves 2 years in prison

- If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve 3 years in prison (and vice versa)

- If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve 1 year in prison (on the lesser charge)”

The way the game is set up, there is a strong incentive to betray your partner in hopes that they remain silent. In other words, you refuse to cooperate with your partner but instead screw them over.

You might think that intelligent people can be more sneaky and better able to “rip people off” and take advantage of them, which would make them less cooperative. And this is true in the short-term – if there is only one prisoner’s dilemma game.

However, when doing repeated prisoner’s dilemmas, high IQ people are more likely to find ways to cooperate in the long-term.

In a different form of this game, participants were awarded different amounts of money but with the same type of schematics in place (choosing to not cooperate while your partner cooperates leads to more money for you, unless you both choose not to cooperate).

- “Economists figured this out in the early days of the field known as ‘game theory,’ that once you turn a one-shot prisoner’s dilemma into a repeated game, it’s possible for selfish players to rationally cooperate with each other, not out of a sense of generosity, but out of pure self-interest.”

Here Garett Jones explains how a repeated prisoner’s dilemma works out among individuals with high IQ:

- “It plays out something like this. In the first round, I’ll cooperate. After that, I just do whatever you did last time. So if you cooperated, then I’ll take a chance on cooperation: I’ll return good for good. If you defected, then I’ll return evil for evil: I’ll defect this time. But if you go back to cooperating, I’ll forget about your unfaithfulness, and I’ll go back to cooperating too. This simple strategy works well for many reasons, but three stand out. First, it opens the door to endless cooperation…but second, it doesn’t leave you open to the possibility of endless exploitation….A tit-for-tat player punishes defection swiftly and smartly. And third, the punishment ends as soon as kindness returns: if your partner mends his ways, you forgive and forget.”

When low IQ people play this game, they will often hold grudges when they are taken advantage of, or try to take advantage of someone after a long string of cooperation.

However, high IQ people are more likely to realize that it’s in their interests in the long term if they both cooperate and continue to reap small but reliable rewards over a long period of time.

This is similar to how many of our interactions are in the real world. We often work with many of the same people on a daily basis (whether it’s at our job or within our neighborhood), so we realize that it’s probably better to build a relationship of cooperation so that we are all better off in the long-term.

Groups of high IQ people tend to be better at working out this cooperative relationship than groups of low IQ people (who are more likely to see the world in terms of “dog eat dog”). You can find the study here if you’d like to learn more.

Of course, at larger scales this can have tremendous implications for how businesses, governments, and nations as a whole build their institutions and work together as a whole.

And indeed, Jones’ research finds that nations with high IQs tend to have less corruption, less bribery, higher trust (and social capital), and more respect for human rights and property.

Because respecting your neighbors’ rights is going to make them more likely to respect your rights as well – forming this long-term cooperative relationship often benefits everyone more over time.

The power of conformity and peer effects

Humans are natural conformists. We often copy our peers in many different ways including sharing the same beliefs, talking in the same way, and how we choose to act and live our lives.

In the popular Asch conformity experiment, participants were asked to look at three different lines drawn on a chalkboard and determine which line was the longest. The key to the experiment was that the room was filled with confederates (those who were “in” on the experiment) and only one actual participant.

Results showed that even when the confederates chose an obviously wrong answer, the participants were more likely to conform to that answer even if they didn’t agree with it.

This shows just how powerful conformity can be in human behavior. Psychologists sometimes call it the “bandwagon effect” – if everyone else is doing it then you figure that you should too.

In this way, surrounding yourself with smarter people is likely to lead to a more positive “bandwagon effect.” Even if you aren’t as smart as your peers, by surrounding yourself with them you are more likely to adopt their “smarter beliefs” and “smarter habits,” simply because that is what everyone else is doing.

Similarly, being around smarter and more motivated people pushes you to be your best self. As Garett Jones mentions in the book:

- “Perhaps this is little surprise: swimmers and runners and athletes of all types know that you’re a bit more likely to train harder when you’re in the presence of stronger athletes. You swim a bit harder when the person in the next lane is swimming faster than you, whether you notice it consciously or not.”

The same is true for employees who are surrounded by smarter employees, or students who are surrounded by smarter students, or neighbors who are surrounded by smarter neighbors.

This is another great example of the synergistic effects of IQ and how they can have a spillover effect on individuals who maybe aren’t as smart, cooperative, or motivated.

While conformity and peer pressure are not often seen as a positive virtue, it can become a positive thing if we find ourselves conforming to beliefs and habits that are actually positive. We can even call this “positive peer pressure.”

Intelligence correlates with patience and economic savings

Just as higher IQ correlates with logical reasoning, problem-solving, and cooperation, research has also show than those with higher IQ tend to be more patient.

In the famous marshmallow experiment, children are asked whether they would like one marshmallow now rather than two marshmallows at a later time. This ability to defer instant gratification for a bigger reward in the future is considered a good measure of patience and will-power.

In similar studies it has been found that this ability to delay gratification for bigger rewards is also highly correlated with IQ.

Bringing this back to the national level, Garett Jones theorized that more patient individuals in a country would also be likely to have higher savings rates. And indeed this is what he found:

- “In the real world, IQ typically arrives bundled with patience, and patience causes savings, so you might think that high-IQ countries would tend to have higher savings rates. And you’d be right. Overall, the global relationship between a nation’s IQ and its national savings rate is moderately positive. And this isn’t just because high scoring countries have better run governments that make it safe to save money: the national IQ to national savings relationship holds when you take account of differences in the quality of each country’s government.”

From an economic standpoint, savings can be a great predictor of economic growth and wealth. When individuals are more likely to save their money (rather than spend it right away), this frees up more resources and capital to invest in long-term projects in business.

Think of it this way: let’s say you have $100 of extra cash to spend every week. If you have low patience, you might be willing to burn that right away on beer, going out to restaurants, or video games. If you have high patience, you can save that little bit each week and eventually buy something far more valuable: like a new car or television.

The ability to delay gratification (and accumulate savings) is very important for being able to cash in on bigger rewards in the future. Due to this, those with high IQ create an environment that is more conducive to economic growth and long-term planning.

Conclusion

Based on all of the findings in Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own, there’s a strong case that IQ matters a lot and is a very strong predictor of better outcomes at both an individual and group level.

It’s still worth noting however that many of these findings are correlations and it can be very difficult to tease out all the causes, especially on a sociological level where many different factors come into play.

There’s still a lot of debate among scientists about how much IQ is influenced by nature vs. nurture, although it’s safe to say that both come into play to some degree. According to the American Psychological Association, IQ is between 45-75% heritable (see here), but that still leaves a lot of room for environmental factors and education.

One thing is certain however, and that is IQ is a very important factor in our everyday lives. And by surrounding ourselves with highly intelligent people, we are likely to get more out of our lives than if we are to surround ourselves with less intelligent people.

This “hive mind” effect is very important to consider in your own life. Who are the types of people you often choose to associate with? And how might they be influencing you in positive or negative ways?

Enter your email to stay updated on new articles in self improvement: