Being “normal” is rare, being “different” is common. We all have different strengths and weaknesses, so we’re all best defined by our individuality.

What does it mean to be normal? What does it mean to be average?

According to psychologist Todd Rose in his book The End of Average: How We Succeed in a World That Values Sameness, there’s no such thing as “normal” or “average.” Everyone has different strengths and weaknesses, and we are all best defined by our individuality.

Throughout the book he does a wonderful job dispelling the myth of “normal” and showing how we can begin to see people more as individuals rather than compare and measure people against some fictional average that never truly captures who we really are.

- “The central premise of this book is deceptively simple: no one is average. Not you. Not your kids. Not your coworkers, or your students, or your spouse. This isn’t empty encouragement or hollow sloganeering. This is a scientific fact with enormous practical consequences that you cannot afford to ignore.”

Our society is very ingrained to think about everything in terms of what is “normal.” We then see anyone who deviates from this label as somehow dysfunctional or different. But we are all different in our own way. Even when we do define what counts as “normal,” it’s very rare that anyone actually fits this description.

Being “normal” is rare. Being “different” is common. This is a fundamental truth about human nature and its infinite variability. I’ll begin this article by showing you how the idea of “normal” is a red herring and then I’ll show you how we can begin to view people as individuals by following three simple principles.

In the late 1940s, the U.S. air force noticed that many pilots were having trouble operating their planes (including a devastating increase in deadly plane crashes). They theorized that people had grown in size since the original design and it was time to remake the cockpits to fit this new average.

They assigned Lt. Gilbert S. Daniels, who had majored in physical anthropology at Harvard, to begin measuring pilots’ limbs with a tape measure and then discover an “average pilot size” so that they could redesign the cockpits with this new information.

Upon completing this task, Daniels discovered the average range of ten different body dimensions. But to his surprise, very few pilots fit this average as individuals:

- “Out of 4,063 pilots, not a single airman fit within the average range on all ten dimensions. One pilot might have a longer-than-average arm length, but a shorter-than-average leg length. Another pilot might have a big chest but small hips. Even more astonishing, Daniels discovered that if you picked out just three of the ten dimensions – say, neck circumference, thigh circumference, and wrist circumference – less than 3.5 percent of pilots would be averaged size on all three dimensions. Daniel’s findings were clear and incontrovertible. There was no such thing as an average pilot, you’ve actually designed it to fit no one.”

If they tried to redesign the cockpits to fit the “average pilot,” it turns out that not a single pilot would fit this average. By trying to create a design that fit most pilots, they would end up creating a design that in reality fit no one.

They had to search for a new solution. And eventually, aeronautical engineers came up with an innovative answer to this problem – an answer that now seems rather simple and commonplace.

Instead of designing a cockpit that fit this fictional “average size,” they would design adjustable seats, adjustable foot pedals, adjustable helmet straps, and adjustable flight suits.

This idea of having an adjustable design is now standard in planes and automobiles. We all own cars that have adjustable seats and mirrors. By creating a flexible design, each individual is able to tailor the vehicle to fit their unique size.

This is just one example of how the myth of normal can inhibit the way we approach problems in life and why we must think of the “individual” to solve life’s complex problems.

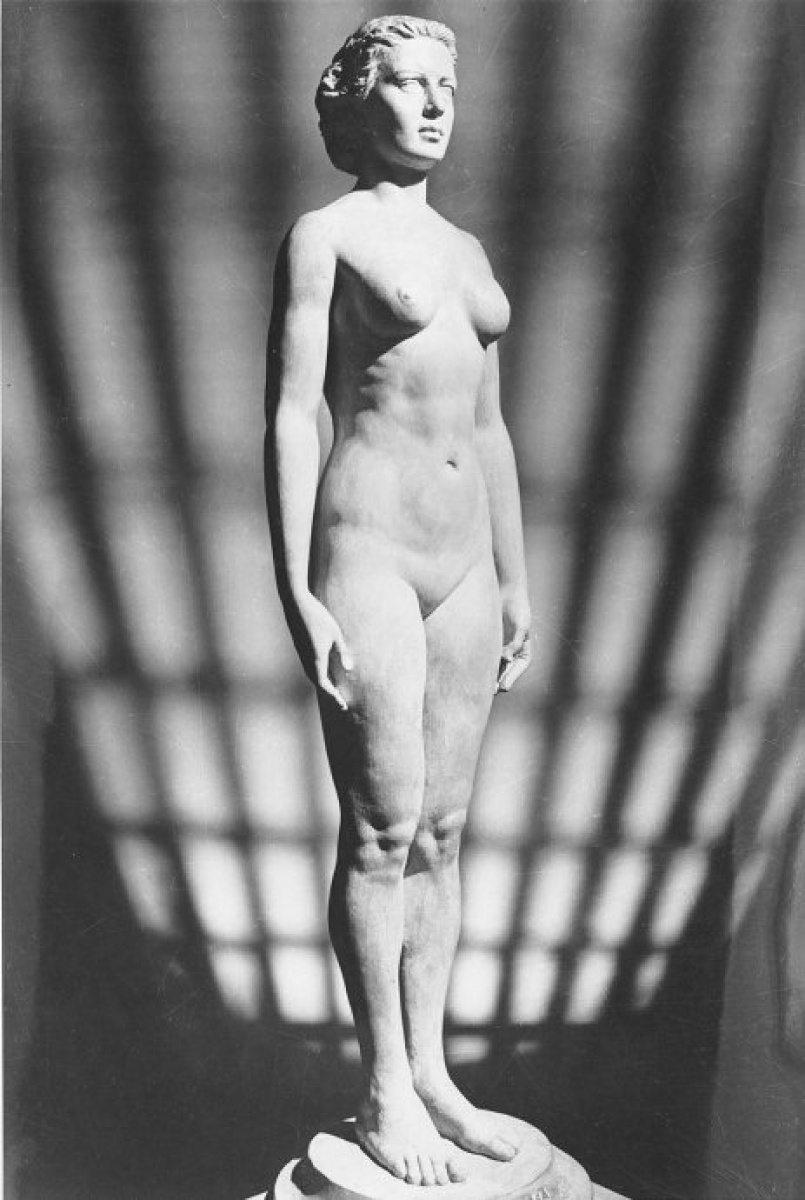

Here’s another example of the myth of normal. Around the same time, an American gynaecologist measured thousands of young women, calculated the average, and created an alabaster model of a typical young female – which he viewed as the “ideal” female size.

This model of the “ideal” female was named Norma. Here’s a picture of her below:

Based on this model, a local newspaper decided to throw a “Norma Lookalike Competition” – the winner would be the woman who best fit these dimensions of the “perfect” or “ideal” physique.

As you can probably expect by now, the results surprised everyone:

- “The reality turned out to be nothing of the sort. Less than 40 of the 3,864 contestants were average size on just five of the nine dimensions and none of the contestants – not even Martha Skidmore – came close on all nine dimensions. Just as Daniel’s study revealed there was no such thing as an average-size pilot, the Norma Look-Alike contest demonstrated that average-size women did not exist either.”

This myth of “normal” or “average” is an important lesson to learn, especially for women who can be very self-conscious of their body size. The simple truth is that there is no such thing as “normal” – human diversity is too great, and we must learn to embrace that more than searching for this fictional ideal of “normal.”

- “Rather than comparing people to a misguided ideal, they could have seen them – and valued them – for what they are: individuals. Instead, today most schools, workplaces, and scientific institutions continue to believe the reality of Norma. They design their institutions and conduct their research around an arbitrary standard – the average – compelling us to compare ourselves and others to a phony ideal.”

Now let’s get into the three principles that help guide us to think of people more as individuals. These principles include: the jaggedness principle, the context principle, and the pathways principle.

The Jaggedness Principle

The first idea we must consider when describing people as individuals is “the jaggedness principle.”

According to the jaggedness principle, no one is solely “normal” or “average,” nor are they solely “below average” or “above average.” As much as we’d like to rank people as “better” or “worse” compared to any given average, the truth is everyone has their own separate strengths and weaknesses.

Here Todd Rose describes more on what it means for a quality to be “jagged”:

- “The principle holds that we cannot apply one-dimensional thinking to understand something that is complex and ‘jagged.’ What, precisely, is jaggedness? A quality is jagged it it means two criteria. First, it must consist of multiple dimensions. Second, these dimensions must be weakly related to one another. Jaggedness is not just about human size; almost every human character that we care about – including talent, intelligence, character, creativity, and so on – is jagged.”

How do we apply the jaggedness principle? By recognizing that every person has unique strengths. A person may be really good at math, but bad at writing – or a person may be good at conversation skills, but bad at critical thinking skills.

The opposite of the jaggedness principle is one-dimensional thinking. This is attempt to take the complexity of human beings and simplify it into one single factor.

One example of one-dimensional thinking is how the NY Knicks were being managed back in 2003:

- “In 2003, Isiah Thomas, a former NBA star, took over as president of basketball operations for the Knicks with a clear vision of how he wanted to rebuild one of the world’s most popular sports franchises. He evaluated players using a one-dimensional philosophy of basketball talent: he acquired and retained players based solely on the average number of points they scored per game.”

Clearly, the team that scores the most points wins. So by stacking a team with only high-scoring players, it seems to make sense that this would lead to the most points and therefore the most wins.

However this isn’t how things worked out for the Knicks. Despite having a team with the highest combined scoring average in the NBA, they suffered 4 straight losing seasons, losing 66 percent of their total games. This one-dimensional Knicks team was so bad that only two teams had a worse recording during the same stretch.

Why? Because basketball is a complicated team sport that requires way more skills than just being good at scoring points. Instead, basketball is often considered a 5 skills game that requires not only scoring, but also other skills like rebounding, passing, blocking, and stealing.

And because human talent is often jagged, players that are good at scoring may not be good at stealing, and players that are good at stealing may not be good at blocking, etc. Out of tens of thousands of players who have played in the NBA since 1950, only five players have ever led their team on all five dimensions.

To build a successful winning team, you have to consider all 5 of these skills and how they work together. You also need to apply the jaggedness principle, which means that some players are going to excel at some skills more than others.

The jaggedness principle doesn’t just apply to physical ability, but also mental ability.

Psychologists James McKeen Cattell at Columbia University theorized that mental abilities would either be “good” or “bad” across the board for most individuals. But after conducting a study of hundreds of college students each year, he found the exact opposite:

- “Cattell administered a battery of physical and mental tests to hundreds of incoming freshman at Columbia University across several years, measuring such things as their reaction time to sound, their ability to name colors, their ability to judge when ten seconds passed, and the number of letters in a series they could recall. He was convinced he would discover strong correlations between these abilities – but, instead, he found the exact opposite. There was virtually no correlation at all. Mental abilities were decidedly jagged.”

The jaggedness principle is very important for understanding individuality. Due to a mixture of nature, nurture, and experience, individuals are likely to be excellent at some physical and mental abilities, while being lackluster in others.

When you consider individuality, you need to pay attention to everyone’s unique strengths and weaknesses.

The Context Principle

The second idea to keep in mind when describing people as individuals is “the context principle.”

The context principle states that people’s thoughts and behaviors are often a combination between both their personality and their situation.

When we try to label people, we are often only taking into account a small sliver of who they really are within a specific environment. For example, when we say that someone is an “introvert” or “extrovert,” that usually depends in what context we find the person:

- “A girl might be extroverted in the cafeteria, but introverted on the playground. A boy might be extroverted on the playground, but introverted in math class. And it was not the situation alone that was the determining factor: if you picked two girls, one might be introverted in the cafeteria and extroverted in the classroom, while the other might be extroverted in the cafeteria and introverted in the classroom. The way someone behaved always depend on both the individual and the situation. There was no such thing as a person’s ‘essential nature.’”

Human behavior always take places within a context. And people can act wildly different in different situations. When we see someone as embodying a particular personality trait, that doesn’t necessarily say anything about their “essential nature.” It could just mean that in that specific context, they tend to act that way.

Knowing this, the book recommends we follow an “IF THEN” strategy when describing the complexity of human individuality. It draws on research from psychologist Yuichi Shoda, who is one of the pioneers of modern day science on individual differences:

- “Shoda summarized his trailblazing findings in his aptly titled book: The Person in Context: Building a Science of the Individual. In it, he provides an alternative to essentialist thinking he calls ‘if-then signatures.’ If you want to understand a coworker named Jack, for example, it is not particularly useful to say ‘Jack is extroverted.’ Instead, Shoda suggests a different characterization: IF Jack is in the office, THEN he is very extroverted. IF Jack is in a large group of strangers, THEN he is mildly extroverted. IF Jack is stressed, THEN he is very introverted.”

By applying an “IF THEN” strategy when describing individuals, we take into account the full context of a person and how they act in specific situations.

(Interestingly, psychologist Charles Duhigg also recommends something called “implementation intentions” that make use of the “IF THEN” format when we are trying to change a specific behavior in a specific context. You can read more about it here: Identify Your Habit Loops).

When you see someone as embodying a specific trait (neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, or extroversion), keep in mind that you might only be seeing them within a limited context, and that this trait doesn’t necessarily define them as a person. It could even be that you are a part of the context that elicits that particular trait.

The context principle is a good reminder because it shows that people aren’t fixed or static beings. No one is a typical “introverted” or “rude” or “lazy” person, because even within these labels there can be a lot of variety.

When we pay attention to the context principle, we often find that people are much more dynamic and changing than we give them credit for. This helps us to recognize the individuality of every person and be cautious of using a single label to define them.

The Pathways Principle

The third idea we need to consider to help us describe people as individuals is “the pathways principle.”

According to the pathways principle, there is no single “normal” pathway for a person to develop and grow. Instead, we all follow our own pathway, which is often shaped by our individual choices and individual experiences.

There are always multiple pathways to the same goal. This holds true regardless of what we’re trying to achieve:

- “We have already seen how averagarian thinking dupes us into believing in ‘normal’ brains, bodies, and personalities. But it also dupes us into believing in normal pathways – the idea that there is one right way to grow, learn, or attain our goals, whether that goal is as basic as learning to walk or as challenging as becoming a biochemist.”

In the book, Todd Rose starts with the example of a baby learning how to walk. Because this is such a natural phenomenon, developmental psychologists have often assumed that every baby’s development follows the same stages and any deviance in this pathway must signal a dysfunction or abnormality.

But upon closer inspection, psychologists have discovered that even something as simple as learning how to walk can often be developed in a number of different ways. All babies learn at different rates, some skip stages, some go back to old stages, but most eventually learn to walk even if they all follow a different pathway.

In fact, even culture can play a big role in the different ways babies learn to walk. For example, psychologists often saw “crawling” as a necessary step toward walking, but later found that in places like New Guinea (where the ground is often dirty and susceptible to germs and disease), babies are commonly discouraged from crawling on floors. However, they do go through a “scooting” phase where they move on the ground while sitting upright.

The pathways principle teaches us to respect different learning processes for each individual. This can have many different implications not only for personal growth, but also education and work-related learning.

In the late 1960s, psychologist Benjamin Bloom did an experiment testing how different groups perform learning a subject:

- “Bloom and his colleagues randomly assigned students to two groups. All students were taught a subject they had not learned before, such as probability theory. The first group – the ‘fixed pace group’ – was taught the material in the traditional manner: in a classroom during fixed periods of instruction. The second group – the ‘self paced group’ – was taught the same material and given the same total amount of instruction time, but they were provided with a tutor who allowed them to move through the material at their own pace, sometimes going fast, sometimes slow, taking as much or as little time as they needed to learn each new concept.”

By the end of the course, the “fixed pace group” achieved roughly 20 percent mastery of the material (which Bloom defined as scoring 85 percent or higher on a final exam). However, the “self paced group” had achieved more than 90 percent mastery of the subject.

Of course, it’s natural that a tutor would help students do better. But one big reason for this success is that the student gets to learn at their own pace and not some standardized pathway based on predefined lectures. This is because some students are going to need more (or less) time on certain aspects of a subject, and it’s important they are given that flexibility to fully master learning new material.

The Khan Academy is a much more recent example of the benefits of “self paced” learning. For those that don’t know, the Khan Academy is a free online educational service that allows students to follow a unique pathway and take their time while learning a new subject.

- “Since Khan records data on each student’s progress, it is possible to track the individual learning pathway of each student who uses the modules. The data confirms precisely what Bloom first discovered more than thirty years ago: every student follows a unique pathway that unfold at his or her own highly individualized pace. The data also confirms that the pace at which any given student learns is not uniform: we all learn some things quickly and other things slowly, even within a single subject.”

This pathways principle applies to all types of learning and skill-building. We all have certain subjects that we can learn faster than others, while other subjects that may take us more time and patience.

Many people also learn certain subjects in different ways. People may prefer lectures, or reading, or watching videos. Some may prefer learning within a group, while others prefer studying in solitude. All of these different preferences are going to shape what pathway is best for you.

In all of life, there are often multiple pathways to the same destination. And because people are different types of individuals, different pathways may work better for you than for others. So don’t get discouraged if you’re follow someone’s advice and it doesn’t work for you – it could just mean that you need to find a new pathway.

Conclusion

Altogether these 3 principles (the jaggedness principle, the context principle, and the pathways principle) are all very important for understanding the differences between individuals, and why no one is truly “normal” in any meaningful sense of the word.

The End of Average: How We Succeed in a World That Values Sameness is a great book that celebrates human differences and human potential in a way that respects individuality. It’s an effective antidote to the myth of “normal” that we are often driven to compare ourselves to.

If you feel like you’ve never really “fit” in with what’s normal – don’t worry – you aren’t supposed to!

Enter your email to stay updated on new articles in self improvement: